San Diego Wild Animal Park Funny Zebra Commercial

ESCONDIDO —

A lot has changed in 50 years, including at the San Diego Zoo's Safari Park.

For one thing, many people remember that the attraction was called the Wild Animal Park until a name change in 2010. The park said goodbye to its monorail 13 years ago, ending a 32-year run of whisking guests over its grounds.

The admission price certainly has changed since opening day May 10, 1972, when guests paid $1.25 to enter. As the park begins celebrating its 50th anniversary, a one-day adult pass now costs $65.

But some things haven't changed. The size of the park hasn't diminished or grown, and still is its original 1,800 acres. The attractions takes about half the land, with the other half a bioreserve of undeveloped acres for coastal sagebrush and other indigenous plants and wildlife in the San Pasqual Valley near Escondido.

Also unchanged is the park's original mission of breeding and conservation, allowing zoos around the world to add to their collections without capturing animals in the wild. From its opening day, the park also has provided visitors with opportunities to see how animals behave in their natural habitat rather than in cages and small enclosures.

"I feel like when you visit the park, you're sort of stepping into the world of wildlife rather than the world of wildlife coming to you," Safari Park Executive Director Lisa Peterson said about how the attraction differs from conventional zoos.

"We have the space to be able to have natural herds and a representation of what it might look like if you were to travel to a range country for those animals," she said. "It's a little bit of a different spin, and it allows you to experience it as it is. And what's great about that is it provides a unique visit every single time because you don't know what you're going to see. You don't know what's going to be out there on any given day, but you know it's going to be amazing and it's going to be exciting."

Peterson said she thinks the park is the only one of its kind in California, and she estimates seven or 10 similar parks exists in the country.

(Photo courtesy San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

)

The San Diego Zoo began in 1916 with the creation of the Zoological Society of San Diego by Harry Wegeforth and his brother, Paul, who together thought it would be a good idea to display the lions and other animals that had been brought to the city for the 1915-16 Panama-California World Exposition in what now is Balboa Park.

As recalled in "Heart of the Zoo," the biography of San Diego Zoo Director Chuck Bieler by Kathi Diamant, the idea of Safari Park began with changing attitudes about zoos in the 1960s. Habitats and animal populations were declining, and zoos were seen as part of the problem because of the practice of capturing wildlife.

Charles Schroeder, director of the San Diego Zoo at the time, saw an opportunity for a second zoo where animals could breed in North County.

Charles Faust, the Zoo's designer, had traveled to Africa and returned with drawings of villages to shape the new park's look. Fencing and moats were created with a private grant, and in 1970 three species of hoofed animals — a South African sable antelope, greater kudu and gemsbok — arrived.

Building the actual park would take a $6 million bond measure, which Bieler campaigned for with Joan Embery, the Zoo ambassador who became famous for her many appearance with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show.

Proposition B, the City of San Diego Wild Animal Park Recreational and Education Facilities Bond Proposal, passed with 75.9 percent of the vote in November 1970, the largest margin of support in the city's history.

San Diego Zoo designer Charles Faust works out topographical problems on a scale-model three-dimensional map of the Wild Animal Park in 1970.

(Unknown)

Lakeside resident Richard Massena, 72, was a San Diego State University student at the time and working part time at the San Diego Zoo when he heard about plans for a new type of zoo.

"I started thinking about it," he said. "Mixed species. Large exhibits. You're going to go in with the animals."

Intrigued, he applied for and was hired as one of the first dozen or so animal keepers at the park, leaving behind his earlier plan of being a school teacher. Instead, his studies shifted to night classes at the San Diego Zoo after long days preparing the new park.

"The Zoological Society put together a course for keepers to go through," he said. "Every kind of animal husbandry program that you could think of to make yourself more knowledgeable, more informed on care of the animals. And all of us in the early days were really, really energetic about that kind of thing."

Massena said the park was looking for a group of people who work hard and do just about anything, including building fences.

In this photo from her high-school internship with the San Diego Zoo, actress Brooke Shields poses with a koala. Shields had a month-long internship with the Zoo and the San Diego Wild Animal Park in 1983.

(San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance )

"They decided to basically put chicken wire around the perimeter fence so predators like coyotes couldn't get through," he said. "We put down miles, and it was all done by hand. You name it, we did it."

The crew worked 8 hours a day, six days a week, but nobody wanted a day off because the experience was so interesting, Massena said.

"One of the best things about the early years of park was that everybody was pretty much on the same page," he said. "Animal keepers, construction, maintenance, we were all one big cohesive team. After work we'd get together and play volleyball or picnic. It was just a fun place to work."

The African Village designed by Faust and the monorail were still under construction when Massena arrived, but everything was complete by opening day. It would be several years, however, before irrigation lines would be installed and grass and trees would grow in the barren area. Until then, water was brought in by bucket, and what vegetation did grow was quickly eaten or trampled by animals, Massena said.

Massena said the first new exhibit might have been the lion enclosure.

"We had to do so many things to make sure they didn't get out," he said. "The monorail bridge went right over the lion exhibit, which was so erosion prone it was kind of scary. You'd have to look down to check the fence lines every day to make sure they were still intact."

In the days before a glass partition separated people from lions, Massena remembers seeing parents setting the children on the edge of the enclosure fence.

"You can't protect people from their stupidity, is one way to put it," he said, thankful there never was an incident.

Richard Massena was one of the first animal handlers at the Wild Animal Park and remembers one ostrich that would attack staff members and once kicked a mirror of a truck.

(Photo courtesy Richard Massena.)

Animal keepers sometimes had their own incidents. Massena said he remembers one ostrich, usually a docile species, having a particular bad attitude.

"He'd come up to the trucks, and I remember him kicking off a side-view mirror," he said. "Every time we would go to the East Africa exhibit, we'd have to find out where he was because he'd go after you."

Massena said animal keepers sometimes had to invent ways to do things, such as the time they figured out how to get a rhino into a crate for transportation.

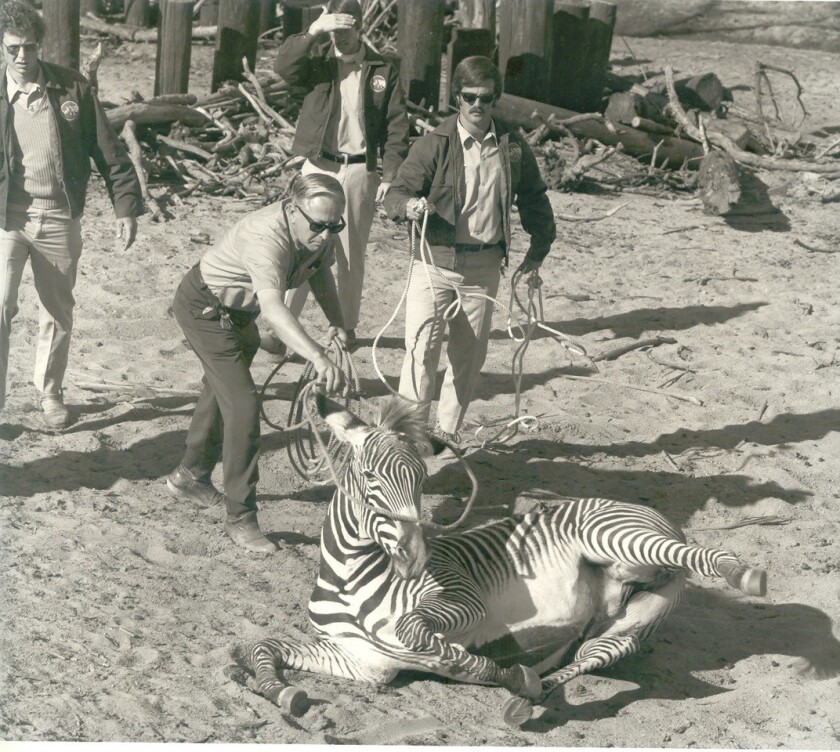

If an animal needed to be captured to treat an injury or for another reason, Massena said keepers would work with veterinarians who would shoot a tranquilizer dart at it. The keepers then would use a lasso on the animal, timing it just as the animal was getting drowsy but not before it hit the ground.

"You want to make sure you're close enough so when it goes down, you can assist that process," he said. "You kind of have to track the animal in a truck, and once it's approachable, you have to use the lariats."

In the early days, veterinarians had to guess at the animals' weight to determine how much to put in the dart, and an under-dose could mean a struggle for the keepers. The technique became more perfected as time went on and vets began keeping track of the animals' weight.

Richard Massena (center, holding rope) helps lasso a zebra at the Wild Animal Park.

(Courtesy Richard Massena.)

At the time, the park would care for animals in what Massena described as a M*A*S*H*-type hospital, which was replaced by a much more advanced hospital about 20 years ago.

Massena's job also brought him adventures outside the park. His first trip out of the country was when he brought Rocky Mountain goats to the East Berlin Zoo when he was about 25. He brought other animals to China, made several trips to Europe and also went to Crimea, where he helped immobilize 110 horses in five days to determine if they were authentic Przewalski wild horses.

When he was 33, Massena would have his most serious on-the-job injury when dealing with a Przewalski stallion. The horse was trying to kill a newborn foal, and Massena had rescued the colt by placing it under a tool box in a truck. The stallion followed him and clamped down on Massena's left forearm, shattering it. A bone graft from his hip and two permanent metal plates saved his forearm. Researchers later learned that Przewalski stallions will kill colts sired by another male horse after they take over a herd, which was not known at the time.

Richard Massena (right), one of the original animal keepers at the Wild Animal Park, had a few confrontations with wildlife on the job. He once was hospitalized after a horse bit and broke his arm.

(Photo courtesy Richard Massena.)

In his time at the park, Massena went from an animal keeper to lead keeper, then animal care manager. In his final seven years, he went back to being a keeper because he wanted to work directly with animals at the new hospital.

He retired in 2007, but said he still regularly goes to the park and visits with former colleagues and new staff members.

Among the legacies of the park is the role it played in recovering the California condor.

In 1986, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service captured the last 22 condors in the wild, and the park's breeding program was successful enough to lead to the release of birds in 1992. There are more than 400 condors in the wild today.

The park continues to evolve, and Peterson said the next edition will be the Elephant Valley project, which will re-imagine the elephant habitat by allowing guests to walk through the area where the monorail once ran.

The park is planning Kenya Days in August, Zoom webinars will be held every Wednesday in August, and a 50th anniversary dinner and talk about elephant conservation is planned for later this year, she said.

Source: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/entertainment/story/2022-05-16/safari-park-turns-50

0 Response to "San Diego Wild Animal Park Funny Zebra Commercial"

Post a Comment